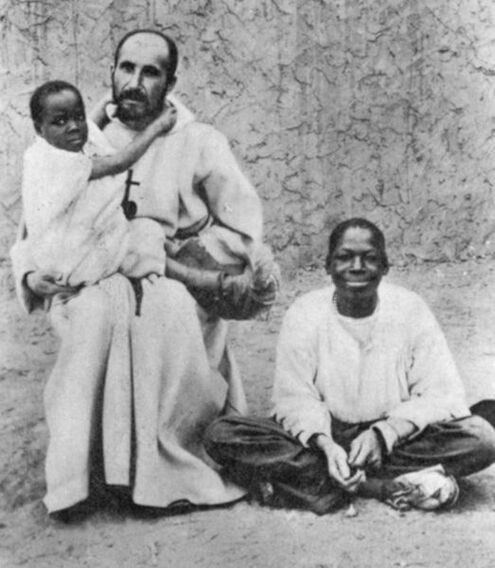

Charles de Foucauld in Algeria, around 1912. Photo courtesy of https://standingcommissiononliturgyandmusic.org

Charles de Foucauld in Algeria, around 1912. Photo courtesy of https://standingcommissiononliturgyandmusic.org I found chapter four of this book particularly edifying. Don Livio Melina, then president of a Roman university specializing in the theology of marriage, sexuality, and family life, speaks on priests as “physicians, healers of wounds.” He points to the “original wound” in every human person, our longing to love and be loved, to understand and be understood, an open wound that never completely heals. Sexual love is both the symptom of that longing and the cure, but even the most fulfilling sexual union is not meant to be perfect. Sexual union itself points to a higher good, like every other good thing in life. Delectable foods, beautiful sunsets, warm human friendships, and every other earthly good is sacramental. It reveals--points to--something greater, but it also modestly conceals that greater good by its own relative goodness.

Holding out for a Supreme Good is a risk, because there’s no “scientific” proof that it exists. What if “sex” is as much as we get in life? What if there’s nothing more than expensive restaurants, fast cars, and cosmetic beauty? Most of us, most of the time, say “a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.” We don’t want to risk losing what we’ve got, even though it is never quite enough. “Postmodern man,” writes Don Livio, “is always in a limbo of indecision because he never definitively risks his life.”

In this age of government safety-nets and technological security, we are trained to avoid risk. But completely eliminating all risk also eliminates human love, which is always risky. For that matter, total “safety” eliminates human excellence in sports, business, politics, and every other human endeavor, which by definition requires overcoming obstacles which could cause serious harm. “Stay Safe” means “Don’t Risk,” which means “Don’t Commit.” We are told to keep our options open and always have a few exit plans.

Priests are ordained for life, without an exit plan, putting all our hope in God’s providence. They do this to be able to heal the original wound in the human heart. His own wound (especially his celibacy, but also his poverty and his obedience) bleeds continuously, pointing him to God, who alone can heal his fundamental wound. Some call priests “wounded healers,” even as the great High Priest, Christ, healed our original wound from his open wounds on the Cross.

Priests today are deeply wounded, along with everyone else. But today, perhaps unlike in previous epochs, Catholic priests see their bride, the Church, hemorrhaging blood and pus. Not only have some clergy proven just as criminal as some politicians and Hollywood moguls, but it seems like almost all of Church leadership has become indecisive, helpless, and hopeless. Is there any hope for a Church that has been proven so feeble?

“I would tell the priest,” Don Livio writes, “to cultivate more and more the hope of the farmer, who sows in difficult times, too, with the certainty that God will ripen the generously sown seed in the fullness of time.” That hope in a future we cannot see or control requires blind trust. It is a risk.

Which brings us to the bookmark that fell out of Don Livio’s this morning. It is the ordination card of a younger priest I greatly respect, Fr. Cameron Faller. He was ordained on June 6, 2015, in San Francisco. He lived a year with us at Star of the Sea and is now archdiocesan vocations director.

“Father,” the card begins, “I abandon myself into your hands. Do with me what you will. Whatever you may do, I thank you: I am ready for all. I accept all. Let only your will be done in me, and in all your creatures. I wish no more than this, O Lord. Into your hands I commend my soul; I offer it to you with all the love of my heart, for I love you, Lord, and so need to give myself, to surrender myself into your hands, without reserve, and with boundless confidence, for you are my Father.”

It is Charles de Foucauld who wrote this prayer. Of French nobility, Charles became a Calvary officer in 1881, exploring North Africa, winning heroic renown as a dashing French soldier. Following a profound conversion of heart, however, he built a hermitage in the Algerian desert, serving the Taureg people. He was assassinated in a Bedouin raid, is buried in El Menia, and will be canonized on May 15. His life marvelously portrays one man’s complete surrender to God’s will, heedless of the risks. He is a mystery that both reveals and conceals the mystery of God. This is what priests are ordained to be: men that take the greatest risk of all, complete surrender to a God no one can “prove” even exists. Not many of us do it very well, but some do, like Blessed Charles de Foucauld, and, I pray, Fr. Cameron Faller and today’s young priests.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed