Mother Teresa often said, “Our poor people are great people.” She saw the nobility of the poor, their superior patience, humility and stamina in the face of grinding adversities that would break most of us. On Wednesday, I spent a few hours in her Rio de Janeiro soup kitchen after giving the sisters a retreat.

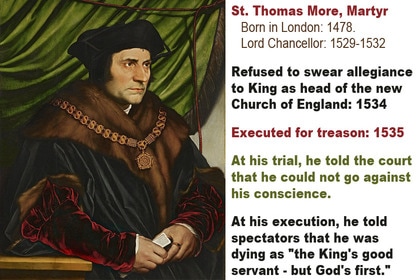

| The sisters welcomed 70 street people at a time into their chapel for a little Bible time before the meal. I obliged the sister by saying a few inspired words in Spanish and giving a blessing in Latin. These beloved street people were overjoyed—they grasped my hands--Pai, uma bênção! and I blessed them again, individually. How their poverty enriched me! Later, in the dining room, over plates heaped with steaming rice and meat, they thanked the good God for giving them another meal. Meanwhile, a second group of 70 had been herded into the chapel, and I was called in for another ferverino in Spanish and blessing in Latin. On my way back from Brazil yesterday morning, I did a holy hour in the nondescript airport chapel in Houston (God bless Texas—it still has airport chapels, and even announces them over the loudspeakers). The only other man in the chapel during my hour was a poor black man, a security guard of the lowest rank, a bit overweight, the invisible poor of American society. He read a little from his bible, then knelt on the floor, elbows on the chair in front of him, head in hands. After a few minutes he got up and went to work. In all the noisy unreality of big airports, this poor man found had found that which is real. Here was true human nobility. As Lord High Chancellor to the mighty Henry VIII, Sir Thomas More had been given great authority in Britain’s political apogee. He was a gifted intellectual, probably the brightest in the realm. And yet he maintained the poverty of belief; he did voluntary penances (a hair shirt and fasting on Fridays) to keep himself poor. Unlike the mighty King Henry, he claimed not ownership but stewardship of his gifts. When he was imprisoned for in the Tower of London for refusing to accept the king’s perfidy, he did not lose his noble serenity. He writes to his daughter Margaret: “I will not mistrust him [God], Meg, though I shall feel myself weakening and on the verge of being overcome with fear. Either he shall keep the king in that gracious frame of mind, or else, if it be his pleasure that for my other sins I suffer as I shall not deserve, then his grace shall give me the strength to bear it patiently, and perhaps even gladly.” St. Thomas does not imagine that it would be easy for him to suffer, but hopes he may bear it patiently, “perhaps even gladly.” Yesterday I saw a lot of poor men in Rio bearing their unjust sufferings patiently, even gladly. Thomas More himself, rich in many gifts, gave them all to God “gladly” in the end. All of us, from the street people of Rio to the power brokers of New York, can attain that same magnanimity by training ourselves in poverty of spirit. On the day that it will all be taken from us, may we surrender it patiently, perhaps even gladly. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed