On Juan Diego’s Day I was reclining on a Boeing 777 between Washington and San Francisco. I watched a movie called The Covenant, about an American soldier who risks his life to rescue an Afghani interpreter who had saved his life. It’s an inspiring war movie (be advised that soldiers drop a lot of f-bombs), but my critical faculty realized how very good Hollywood has become at glamorizing assault weapons. The American movie industry knows just how to evoke the heart-thumping desire in a man to wield immense personal firepower (all in the cause of good, of course). Very few see the irony of media elites making lots of money by both glorifying assault weapons and demonizing assault weapons at the same time. I looked around the plane at what others were watching. Almost every movie portrayed people toting impressive assault weapons. To an angry young man, the scene in which an American AC-130 gunship wipes out the Taliban fighters like a sponge wipes ants from a kitchen countertop is a virtual training video on how to wipe out a school classroom. Hollywood is training people to shoot up schools and post offices. The Covenant is an impressive war movie, and innocent people need to be protected, but should we soak ourselves in these portrayals of violence?

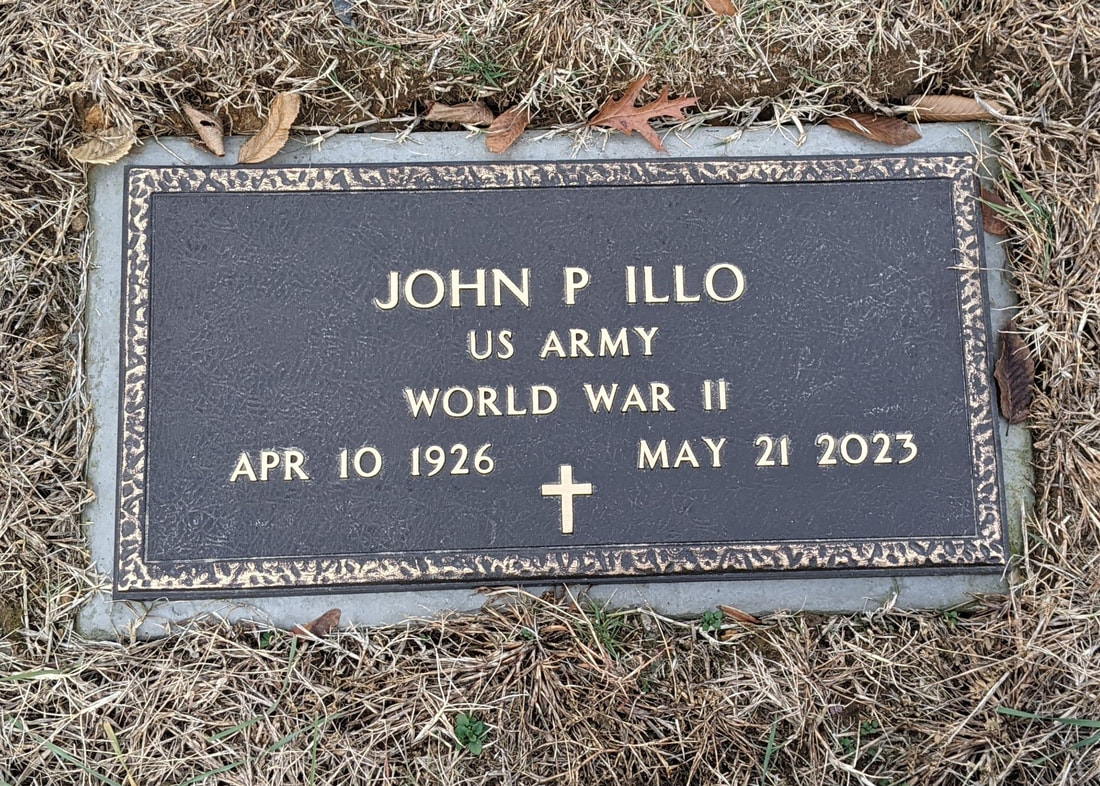

This Boeing 777 was returning me from a visit with my family in Pennsylvania. While in my hometown, I prayed at my parents’ graves as a bitter wind drove snow flurries into my eyes. Dad had served in the US Army from 1944-1946, mostly in Manila where Japanese guerilla cells held out for some weeks after the surrender. My Father hated violence, and whenever he heard guns firing on TV he would march into the living room and turn the set off. My Dad had seen real violence, and he knew that it must be the last resort in self-defense. But we soak ourselves in virtual violence. We enjoy it.

Juan Diego was a small man from a big empire built on violent conquest. His Aztec rulers practiced ritual human sacrifice and ate the flesh of their enemies. Their art portrays the gods as angry, open-jawed consumers of human flesh. Juan Diego, however, made a choice, with God’s grace, to reject this dreadful culture of violence. He believed in “the one True God by whom all things live,” in the tender words of the beautiful lady who appeared to him. Juan Diego spent the rest of his life as the simple caretaker of a small chapel which housed his old tilma, a simple piece of corn fiber cloth that bore the image of a woman clothed with the sun. She bore in her womb the Son of God, and Juan Diego trusted in this God, who made himself a baby so that babies would no longer have to be sacrificed on the altars of human pride. Juan Diego died on December 9, 1548, seventeen years to the day that he had first seen the beautiful lady. He died a happy man.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed